I would like to introduce…Kibera News Network, Kibera’s first TV news station. Featuring online content produced by 16 youth from Kibera!

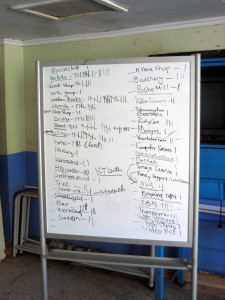

Last week, we began training 16 enthusiastic youth on Flip cameras. We haven’t quite got the internet installed at KCODA for the uploading, so we’re not online yet. But I can’t wait. Just see below all the amazing stories that the teams are planning to report on. They have already started and I’ve seen some great footage! THESE are some of the stories that are hidden inside the slums waiting to be told. Notice that most groups categorized stories into themes (and some only had themes, so we will work on that).

Group 1:

Collins, Moha, Steve

1)Â Â Â Noise pollution: the noise rules are not followed; during day it is very noisy due to business activities like CD shops.

2)Â Â Â Olympic bus terminus: the bus turn about was repaired but it not used (waste of municipal funds?)

3)Â Â Â Need for bumps along chief’s camp road: speeding vehicles are dangerous to school children

4)Â Â Â Dangers of living along the railway lines: possibility that train will fall on them, endangering their lives

5)Â Â Â Grabbing of land meant for pavements and paths: no room for pedestrians due to building out into slum road

6)   Youths and illegal gangs in Olympic – repairing your structure often requires bribe payment to them

7)Â Â Â Interference of power transformers by residents: those who live in kibera often replace the fuses themselves: this causes fire to houses such as that last week of several homes

8.   Insecurity: Bars operate till very late, so they can harbor criminals

9)Â Â Â Presence of local artists who promote peace: like solo 7 and maasai 2

Group 2:

Regynnah, George, Eddie

1)Â Â Â Talents: profiles of especially talented youth: youths playing football, singing, other

2)Â Â Â Security: adopt-a-light program and how it has helped security since lights are now available in some areas, also chief’s place improvements that improved security

3)Â Â Â Education: in Kibera there are some very good schools like Olympic that is top in country, and Soweto academy: profiling top schools in slums

4)Â Â Â Unity: in case of fire outbreak, people unite to help each other and don’t wait for fire truck – team firefighting in kibera

5)Â Â Â Love: people don’t allow each other to go hungry, neighbor will give food if someone needs it

6)Â Â Â Informed: we as youths of kibera are well informed about our rights, not ignorant

7)Â Â Â Fighting poor sanitation: there is a cleanup process where youth gather together and clean the villages themselves

8.   Fighting poverty: many people are self-employed, own their own kiosks and do not work for others

9)   Self-reliant: Those in Kibera do shopping in Kibera, not Nakumatt – one can just get the same items cheaper here and that way the money stays local to Kibera

Group 3:

Mildred, Jacob, Shadrack, Sizzah

1)Â Â Â Sanitation: community health and garbage collection

2)Â Â Â Education: outsiders think Kiberans are not literate and educated; showing that is not true

3)Â Â Â Development: community initiatives that are trying to improve Kibera

4)Â Â Â Recollection: sports and events, community activities and talents, fun

5)   Lifestyle: poverty – people are sometimes wealthy but staying here anyway – inside their mud houses you find nice things they have bought.

6)Â Â Â Housing and land

7)Â Â Â Human Rights

8.   Intercultural and Religious: People intermarrying among tribes. Others think they cannot stay together due to election violence. Is this a problem since 2008?

9)Â Â Â Disease

10)Â Â Â Skills, Knowledge:Â one man built a vehicle for himself in Kibera using scrap metal alone – profile of entrepreneurship

Group 4:

Isabella, Wilfred, Hassan

1)Â Â Â Biogas projects coverage

2)Â Â Â Youth group activities documentation

3)   Sanitation – water taps and toilets

4)Â Â Â farming produce in sacks – new method for business and fighting hunger

5)   poultry farming – can get financially stable by chicken farming in Kibera

6)Â Â Â lobbying and advocacy

7)Â Â Â kazi kwa vijana: jobs for youth program follow up – is it working? have youth found jobs?

8.   security

9)Â Â Â expansion of roads and impact that is having – some people are being pushed out

10)Â Â Â hospitals establishment: residents use local clinics not Kenyatta hospital – plenty of local health services now

Group 5:

Cliffton, Douglas, Lucy

1)Â Â Â Sanitation: UN toilet compared to CDF funded: comparison of quality

2)Â Â Â Education: informal vs formal schools – quality comparison

3)Â Â Â Health: how people approach public health and facilities

4)Â Â Â Transport infrastructure: looking at roads inlets and outlets

5)Â Â Â Business: kinds of businesses that exist here, commodities produced.

6)Â Â Â Drainage system: sewage disruption in gutters caused by blockages leading to home flooding, yet sewer lines run right under Kibera without servicing it.

7)Â Â Â Housing: slum upgrading project and how are initial structures looking

8.   Public health: Food kiosks: whether environment is sanitary at these kiosks

9)Â Â Â Water: toilets built along water channels, drainage creates disease

10)Â Â Â Tribes: enclaves: conflicts because people are now living in different areas not mixed. How this happened, makes it easy for attacks on tribes since you know who is who.

11)Â Â Â Land issue: no one has title deeds which causes major problems

After that, we mostly slept, ate and lounged in the cabin known as a banda. Not bad. It’s funny, though, watching the groups of tourists come and go from such a place. It reminds me that the tourist is often so isolated from the environment, kept separate by design- nice Kenya, pretty things to see, eat and drink, hakuna matata, no problem. It is so much more interesting to know the story of where you are, who lives there, what happened to this place during and after colonialism. In Kenya I notice touches of Britain everywhere – and even the colonists themselves and their descendants are still around, if lying low – like a quiet but powerful animal sated and enjoying its repose. I find it decidedly strange. In a resort area like Naivasha, they serve brown sauce and fat sausages and beans for breakfast. The camp that we vacated initially was owned by a white Kenyan family. What’s their story, why have they stuck around, and how exactly do they fit in – or not – with the rest of Kenya? – these questions fascinate me here. In India one finds British influence everywhere – maybe even more so – but as for British people, well, they’ve long since fled.

After that, we mostly slept, ate and lounged in the cabin known as a banda. Not bad. It’s funny, though, watching the groups of tourists come and go from such a place. It reminds me that the tourist is often so isolated from the environment, kept separate by design- nice Kenya, pretty things to see, eat and drink, hakuna matata, no problem. It is so much more interesting to know the story of where you are, who lives there, what happened to this place during and after colonialism. In Kenya I notice touches of Britain everywhere – and even the colonists themselves and their descendants are still around, if lying low – like a quiet but powerful animal sated and enjoying its repose. I find it decidedly strange. In a resort area like Naivasha, they serve brown sauce and fat sausages and beans for breakfast. The camp that we vacated initially was owned by a white Kenyan family. What’s their story, why have they stuck around, and how exactly do they fit in – or not – with the rest of Kenya? – these questions fascinate me here. In India one finds British influence everywhere – maybe even more so – but as for British people, well, they’ve long since fled.

There is really no way to know quite what to expect in advance when you’ve entered a new culture. Even operating in English, signals are uninterpretable, people hard to read, and I sometimes feel that all the

There is really no way to know quite what to expect in advance when you’ve entered a new culture. Even operating in English, signals are uninterpretable, people hard to read, and I sometimes feel that all the