Community Mapping is not a new term, but it seems to be enjoying a makeover due in part to the impact of new citizen-led mapping efforts, like Map Kibera, GroundTruth, and others using OpenStreetMap all over the world. It’s been popping up everywhere lately, so I thought it might be time to look into just what IS community mapping, exactly?

Policy Link reported back in 2002 that:

The terms community mapping and GIS are often used interchangeably. We define community mapping as the entire spectrum of maps created to support social and economic change at the community level, from low-tech, hand-drawn paper maps to high-tech, database driven, internet maps that are dynamic and interactive.

Meanwhile, an organization called Center for Community Mapping uses mostly Google maps to build software and then license it to others to use, with the expressed purpose of “empower(ing) grass-root stakeholders with mapping technology to foster participatory planning, community education, and cooperative organization”.

The first definition above is very broad, and doesn’t say anything about the role of community members themselves; the second does talk about empowerment but does not use open data standards.

Mikel recently presented and posted about this topic, saying “…the excitement of community mapping is beyond the data that’s being created, but the possibility of a fundamental shift in the power dynamics of how development is practiced. If people know the facts about their own lives, they have more power to call to account those institutions which are supposed to serve them, and ultimately, to improve their lives themselves.”

That’s the beginning of our approach. But, to be more explicit, here’s the GroundTruth take…

Frequently Asked Questions about Community Mapping:

Does Community Mapping need to involve the community, in the mapping?

Yes, it does. In the first definition above (the one that equates CM with GIS) it’s more about “mapping of a community” than “community mapping”. To me, that’s just plain mapping. Or perhaps, using GIS to understand a place, which happens to be a particular neighborhood.

Does that community actually have to live in the place where the mapping is happening? Isn’t it enough if they’re from somewhere nearby?

I’d again be pretty strict about that. If it’s called Community Mapping, people should be mapping in their own community, not the one next door. Why? Because we believe this is about participation, and not just about data collection. It’s also about giving people a chance to show what’s happening in their neighborhood from their point of view, in this case through the medium of a map, and about their own use of the information later.

How about if other people map the community and then later involve members of the community in a presentation about the mapping, is that still community mapping?

Not really. It’s just mapping, again, that happens to take place in a community.

Does the community need to own the information collected during the community mapping? Does it have to result in open data?

They don’t need to own it, but we do believe in free and open data as a critical part of community mapping. After all, the point is not to help companies build their commercial base, or to hand over more information to proprietary silos inside NGOs and governments, never to be seen again. The idea is to create a commons of information that can lead to greater transparency from the local level on up, and allow many people to leverage that information.

So, Community Mapping is another way of saying, “the community is actually doing the mapping”. Does that mean they’re using the technical tools themselves? Isn’t that too hard?

In our experience, most people learn quickly to use basic mapping tools, within reason. If students from a nearby university, none of whom live in the community, do the mapping, or if a great local NGO decides to map the local slums, hiring professionals or finding volunteers or using their own staff, none of whom reside in the slums, then that’s not community mapping. If people get their hands on the tools and learn to make the maps (as part of a larger process of participatory planning, information-based advocacy, or other local processes) that’s how we define the CM practice. Yes, we’re going pretty far here in saying that people actually do some technical work rather than perhaps walking around with a more “expert” mapper showing them what is where. There are probably ways that some technical support can be integrated, and certainly not everyone in the community needs to be doing the mapping. But it is part of the premise of OpenStreetMap, that such resources can be created by crowdsourcing, and they make it easy enough to do so.

It’s possible that community mapping can happen without a lot of technical training, though, and using different paper-based integrations (walking papers, etc). Perhaps the key point to make here is, if the goal of your project is explicitly to do community mapping, don’t assume that residents can’t or won’t want to do it themselves. And, as long as your project is done in such a way that prioritizing community empowerment and participation (and check on this carefully; it’s not common), coloring outside the lines of this FAQ is very much encouraged.

If I’m using OpenStreetMap, isn’t that automatically community mapping?

No. It’s great that you are using this user-generated free and open map of the world, though, and thereby contributing to the liberation of data worldwide for generations to come. Please don’t stop. And you might be doing community mapping, but not necessarily.

Is Community Mapping the same as Citizen Mapping?

The name is cleverly different from community mapping. While they could be the same thing, it’s interesting to consider that citizen mapping might imply less of a community-based process, and align more with movements like citizen journalism, imagined to be something done by individuals using their personal mobile devices and things like that. However, in places we’ve worked, that’s not quite how citizen media works either. At this point, I believe the terms can be used interchangeably, and we have definitely used both terms.

Does Community Mapping need to be Open?

I suppose not. But if it’s not, why not? Is it because some of the information collected will endanger a person’s rights in some way, infringing on privacy (household ownership data might)? If not, then yes, it should probably be open. Why? It’s a public good. This might require a fuller debate, but unless the community comes together and decides based on a clear understanding of the implications of free and open vs. private data that they need to restrict access, open should be default.

Does Community Mapping need to involve Citizen/Community Reporting or Media?

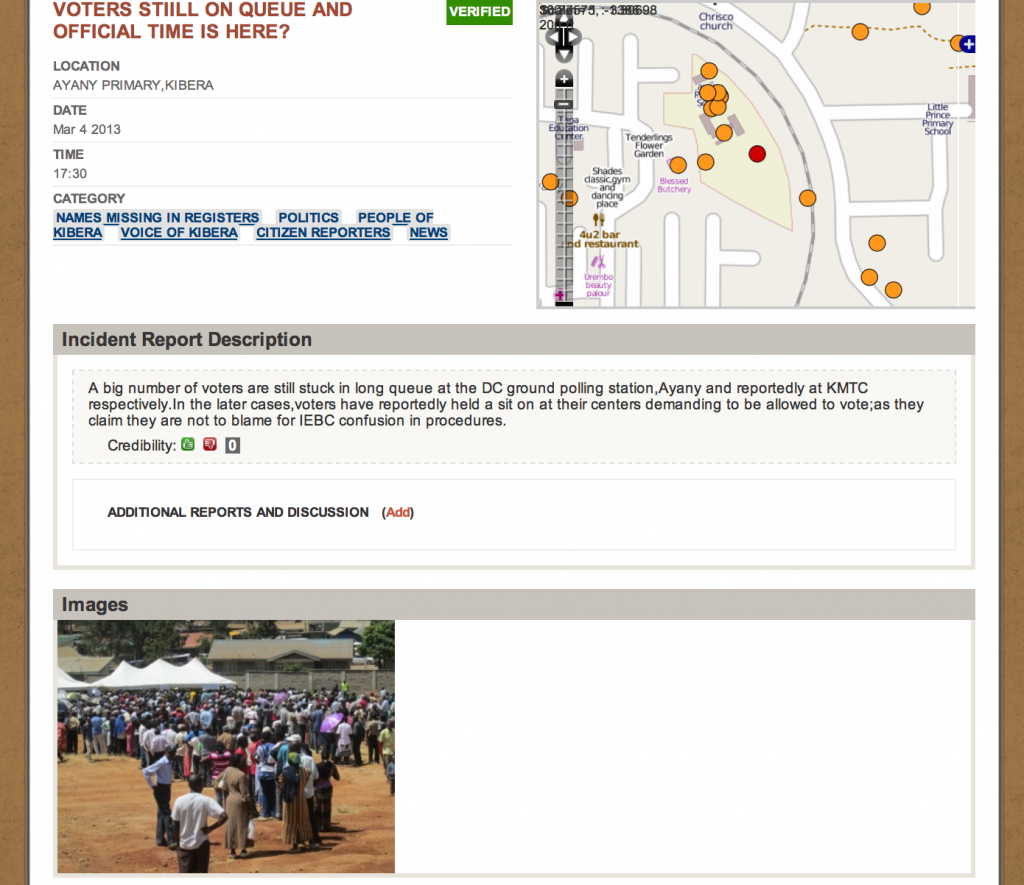

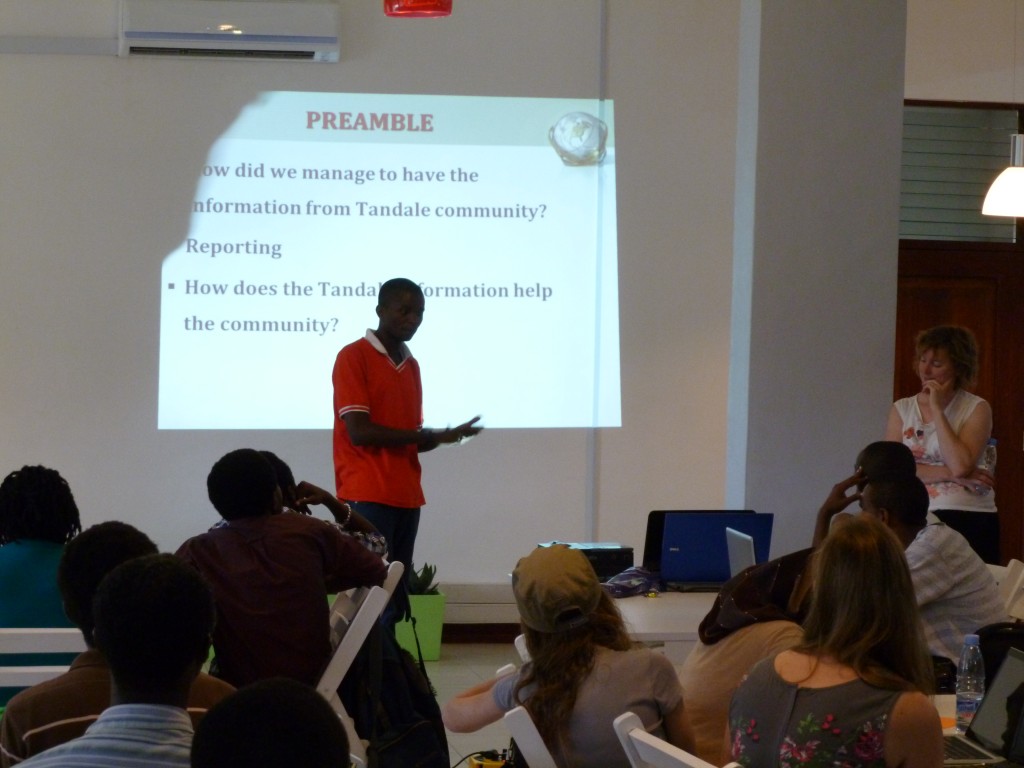

It is important to have a well-thought-out means for people that are making maps to use the information and build off of that base. A very effective way to do that is to introduce different kinds of reporting tools. This is because people get excited about their neighborhood and have more to say – the map can’t really finish the job, it’s just the beginning. Also, there’s a story (or several) behind each point of interest. I can imagine there are other ways that people can really engage around what they are seeing and use it, but the point is to go beyond the map somehow and allow people to tell stories with the data. Using something like Ushahidi or basic blogging and citizen journalism to illustrate community perspectives has been exciting in our work – in part because it is not restrictive about what people may want to say about themselves.

Is this the same as Participatory GIS?

Not quite. Participatory methodology should be part of both and PGIS is one of the inspirations for our work; community empowerment is also key to both. Traditionally, though, PGIS is closed and the information gathered in the process not intended to be shared openly (for re-use, etc). Also, that process doesn’t typically impart the technology skills to the participants.

So what exactly IS community mapping? Briefly.

Here’s my shot at the criteria.

1) Community creates/gathers the map data. That is, geographical coordinates alongside any other information (we’ve collected things like number of nurses in the health clinics, all the way to why one mother takes her child all the way to the other side of Kibera to see a doctor and what path she uses to avoid the street thugs).

2) Community also edits the map data themselves, and comes to agreement on the final product.

3) Mapped information is generally shared openly, online, contributing to commons, unless otherwise specified by the community and after a good discussion of the options.

4) Community uses the map afterwards, themselves. This might be the biggest challenge in practice, but there are plenty of people who have been using maps in local development for many years who can support on this point. We recommend introducing storytelling and media around the data through other tools for online expression. The mapping also can be part of a larger participatory development, local planning, or advocacy process.

Is community mapping the easiest/most efficient way to get the map I want?

Not always! In fact, it’s a time-consuming, complicated, logistically challenging, and just plain difficult way of getting a map made. But, getting a truly good map is usually time-consuming and difficult. Don’t forget, it’s the locals who know what and where everything is in the first place. Here you have to distinguish between the tendency to want a quick result, and the actual usefulness of what you want to produce in the long run. The idea with community mapping, when it uses OSM in particular, is that the resulting maps can be easily updated down the road when things inevitably change. You’re investing in creating local skills and a local network of mappers. Of course, you’re also investing in empowering citizens, but even if you just want your map this is a good way to make sure that the map isn’t useless in five years.

You can ask anyone who’s done one of the following things: community organizing, community development, participatory development, for a fuller explanation of the long-term benefits of the process and their challenges. We would place community mapping inside this constellation of methodologies.

But, what’s the point of making the map, if locals all know where everything is? Aren’t maps mostly for government planning or getting from place to place?

Well, not anymore. We think people can influence that planning (or cause it to happen at all) by doing community mapping. And, well, there’s a perhaps less celebrated motivation here for doing this mapping/reporting/making oneself “visible”. It’s been our exciting experience that people really care about having the truth about their lives come out and be heard, seen, verified, in essence validated. Of course, we’re working with communities that are in some way disenfranchised, but so are many others who would want to do community mapping. We started out (with Map Kibera) investigating the interest in, motivation and usefulness of these tools by people in the community, so I’m really looking at what I’ve seen matter to them.

I welcome your feedback and comments, below. Please discuss with us!